a commission for The Economist -1843 Magazine July 2022 issue.

Red Riding Hood

What was she called, before she put on the garment that supplied her name? And why no horse to wear it on, Red Riding Hood would have asked? She was an inquisitive girl. But we know from our earliest childhood that this is a story that shouldn’t be questioned. The answers are too bloody to share with someone you’re tucking up in bed. Red is violated virginity. She’s rebirth. She’s from a long line of indigestible women, who went into the forest and survived. That wolf didn’t stand a chance.

Bonnet de liberté

The shape is ancient. Slaves freed by Rome had their heads shaved and crowned with a conical hat in honour of the goddess of liberty. But the sans-culottes chose the colour and wore it to storm the Bastille. Like all smart Paris fashions, these hats travelled – American Republicans and abolitionists marched in them; the sculptor Hiram Powers tried to put one on the Statue of Liberty. Today’s French insurgents prefer yellow vests. A less powerful choice, perhaps, than the red teardrops that formed a tide that drowned the monarchy.

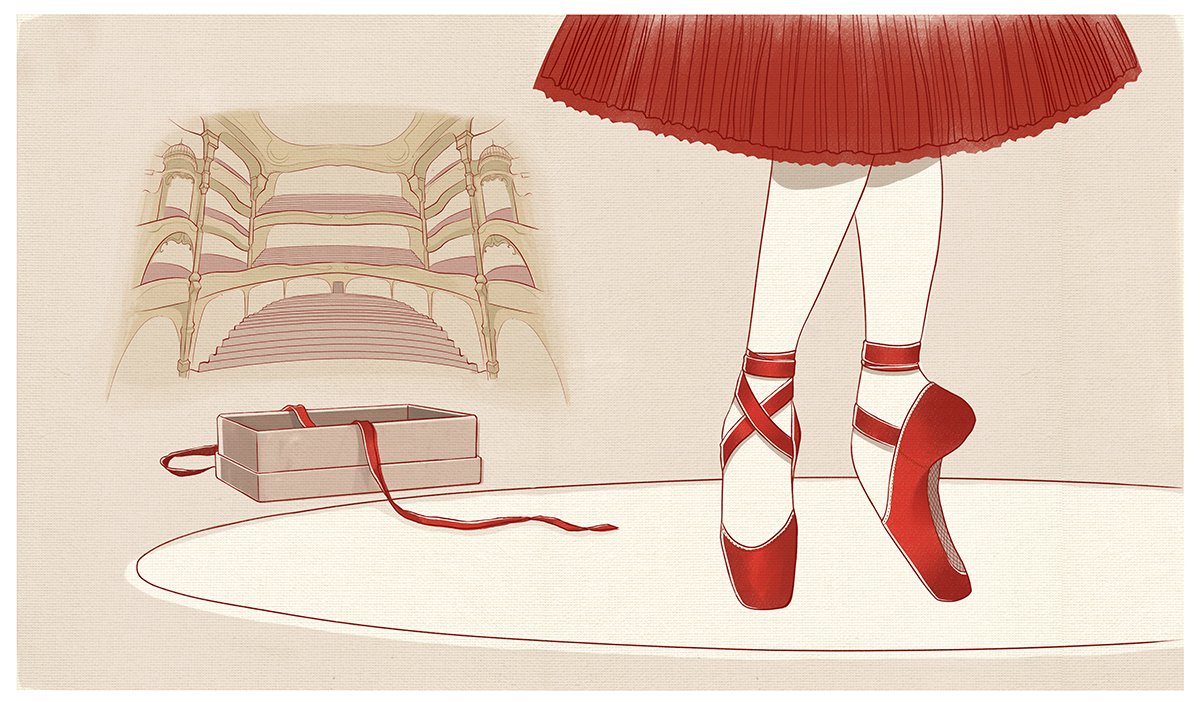

The Red Shoes

We can tell this story with three women, three kinds of magic. In the Oz books, Dorothy’s slippers are white. Technicolour demanded something stronger and more fitting for footwear prised from the corpse of a Wicked Witch. Hans Christian Andersen’s Karen brings her own wickedness: she wears red shoes to church and they then become an instrument of torture. When Michael Powell put the story on screen in ballet form it became a fable about the demonic power of art. “Why do you want to dance?” asks the impresario. “Why do you want to live?” the dancer replies.